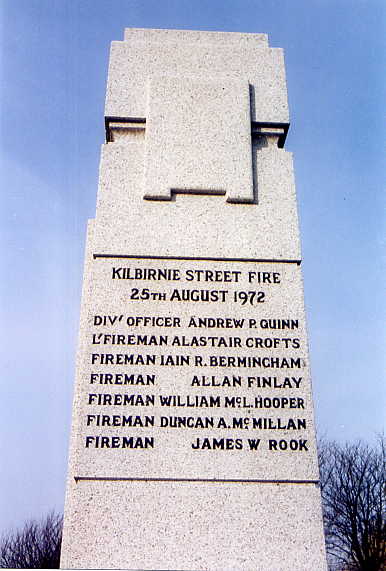

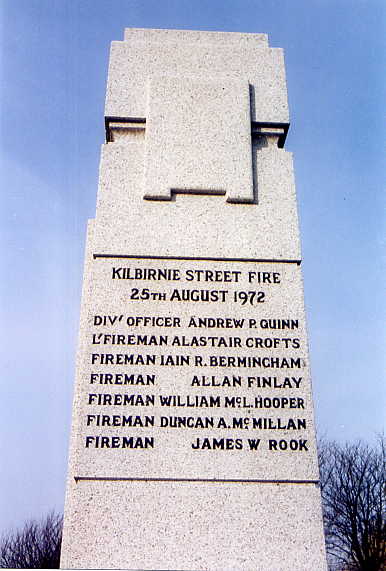

KILBIRNIE STREET FIRE

The South Face of The Cheapside Street Memorial, Glasgow Necropolis. C320/13 16/3/2003.

A salute to brave men

Words do not come easily when one

tries to pay tribute to firemen who have died on duty. Sadly one reflects that

by now one should have had practice enough — that Britain’s firemen, and their

families, always live in the shadow of death and that from time to time one of

our colleagues has to pay a terrible price for the work he does in protecting

society from the ravages of fire.

When seven fire-fighters die in a single tragedy the sense of shock is replaced

by a numbness. Why, one asks, why?

Exactly what happened at the Kilbirnie Street, Glasgow, warehouse is to be the

subject of a fatal accident inquiry. Some of the circumstances are known and are

reported on elsewhere in this issue. What is clear is that the men died in

accordance with the high traditions of the service — traditions of dedication to

duty and help for others. In this column we salute the men who died:

DIVISIONAL OFFICER III ANDREW P.

QUINN

Aged 47, married. South Division. He joined the service in 1948.

LEADING FIREMAN ALISTAIR CROFTS

Aged 31, married with one child and a second child expected. Pollok Fire

Station. He joined the service in 1963.

FIREMAN lAIN R. BERMINGHAM

Aged 29, married with one child and a second child expected. South Fire Station.

He joined the service in

1964.

FIREMAN ALLAN FINLAY

Aged 20, single. South Fire Station. He joined the service in 1971.

FIREMAN WILLIAM M. HOOPER

Aged 44, married with five children. North West Fire Station. He joined the

service in 1952.

FIREMAN DUNCAN A. M. McMILLAN

Aged 25, married with one child. South Fire Station. He joined the service in

1971.

FIREMAN JAMES W. ROOK

Aged 29, single. South Fire Station. He joined the service in 1970.

The loss to their families is

immense and we grieve with the widows and children and parents who remain. The

loss to Glasgow Fire Service is self-evident — whether it is of a Divisional

Officer with almost a quarter of a century’s experience or of a 20-year-old

fireman who joined the brigade only last year.

That the sense of grief is shared throughout Britain is shown by the

contributions that have been made to the Fire Services National Benevolent Fund.

Many have come from firemen themselves; much has come from the general public,

including businessmen giving such sums as £5,000 and £1,000, a prisoner in

Wandsworth who sent £2 and some children who raised £4 in a cake-and-candy sale

in their back garden.

NO SEPARATE FUND

May we here express our approval of

the decision not to set up a separate fund for the dependents of the Glasgow

fire-fighters. The urge to do so is understandable — particularly among the

people of Glasgow itself — but we are sure that most members of the Fire Service

would agree that the scale of help for the families of those who die should not

depend on the scale of the tragedy which cost them their lives.

Understandably, the death of seven men hits the national headlines, but even as

that news was being printed the body of a Birmingham sub-officer was being

recovered from the debris of the factory in which he was killed while fighting a

fire.

So there is another name to inscribe on the roll of honour of Britain’s Fire Service, the name of:

SUB-OFFICER DEREK ANDREWS

Aged 32, married with two children, aged 11 and seven.

In conclusion we would borrow the words of the Secretary of State for Scotland, Mr. Gordon Campbell, MP, in a message he sent after the Kilbirnie Street tragedy to Glasgow’s Lord Provost, Mr. William Gray, and to Firemaster George Cooper: “This is a tragic reminder of the debt we all owe to men of such heroism, who perform a public service we can never take for granted.”

GLASGOW’S KILBIRNIE STREET TRAGEDY

Seven Glasgow fire-fighters died

during a fire at a cash-and-carry textile warehouse in Kilbirnie Street in the

Eglinton Toll area of the city, on Friday, August 25, 1972. Their names are

listed with FIRE’S leading article on the tragedy on page 211.

Six of the men appeared to have formed a rescue squad which went into the

building to rescue the seventh, who had been trapped by falling debris. A fatal

accident inquiry is to be held during October.

The fire incident was described as a “routine call” to a major incident

involving the second storey and roof of the warehouse.

Three appliances, including a turntable ladder, attended after the call at 11-25 a.m., and two reinforcing appliances were requested for BA purposes. The staff of the warehouse had already been safely evacuated by the time the first units arrived and normal fire-fighting procedures were initiated.

Turn to pages 230 and 231 for pictures of the Kilbirnie Street fire.

At about 12-00 there was a fall of

debris and three firemen were led away by colleagues, two suffering from burns

and one from smoke and heat exhaustion. One was revived on the spot and the

other two taken to hospital, where one was detained.

A fourth man remained in the building and it is believed that he had been

trapped by the debris.

Further reinforcements were requested and the six-man rescue team started to

search for the trapped man while fire-fighting efforts were renewed.

According to an official police statement, soon after there was a “blow out” as

a result of which part of the roof appeared to have fallen on the rescuers.

Command of the fireground was taken over by Deputy Firemaster P. McGill — who,

as a Station Officer, was awarded the George Medal in 1960 for his gallantry,

leadership and devotion to duty at the Cheapside Street whisky bond fire and

explosion in which 14 firemen and five men of the Glasgow Salvage Corps died —

and Firemaster G. P. Cooper, on holiday in Argyll, returned to duty and went

straight to Kilbimie Street.

The following day an emergency meeting of the city’s police and fire committee

was called by Lord Provost W. S. Gray to “very seriously” consider the whole

question of fire prevention.

Later the committee announced that it had set up a special sub committee to

review fire precautions arrangements throughout the city and to seek the views

of various organizations and interested parties, including the Fire Brigades

Union.

In addition to this Mr. F. McElhane, MP for the Gorbals, in whose constituency

the tragedy occurred, said he would be calling for a full debate in the House of

Commons on fire legislation.

Glasgow’s police and fire committee also announced that it had received a report

from Firemaster Cooper that negotiations were at an advanced stage for the

installation of a computer at brigade headquarters to store information relating

to the contents and fire precautions arrangements at all industrial and

commercial premises throughout the city.

A final decision on the type of computer to be installed, and the associated

equipment which will be carried on fire appliances, is expected within the next

few weeks.

The committee has also agreed to contribute £1,000 annually to the Fire Services

National Benevolent Fund.

The day after the tragedy the Lord Provost announced that he had decided not to

launch a disaster fund for the relatives of the seven fire-fighters. Instead, he

hoped people would give generously to the Benevolent Fund.

One of the reasons for this decision, he said, was the feeling in the fire

service as a whole that the benefit of public subscription should go to the

relatives of all firemen who lost their lives and not just to those involved in

events which achieved national prominence.

Two days later, on August 28, Lord Provost Gray announced that he had already

received donations amounting to more than £4,500, and by September 4 the total

had risen to over £13,000.

Firemaster Cooper later said that Glasgow Fire Brigade had set an initial target

of £30,000 and to achieve this a number of events were being organized,

including a glittering film premiere at the city’s Odeon cinema on October 28.

Throughout the UK many civic authorities, commercial and industrial undertakings

and private citizens have made or promised donations. A contribution of £1,000

was made by the Action for Disaster Fund, set up in Scotland less than a year

ago after the disasters at the Ibrox football stadium and the Clarkston shopping

precinct.

Representatives from every public fire brigade in the UK — including the Channel

Islands and Northern Ireland — attended the funerals of the seven victims.

A Requiem Mass was offered for DO Quinn at Holy Cross Church, Crosshill, by

Bishop Ward, vicar-general of Glasgow’s archdiocese, and at Glasgow Cathedral

the Rev. Dr. W. Morris conducted the funeral service for the other six men.

During both services appeals were made by the clergy for action to ensure that

there could be no repetition of the tragedy.

Some 3,000 mourners, including an estimated 500 firemen, were in the Cathedral

and loudspeakers relayed the service to a further 2,000 outside. Among 14

lorry-loads of wreaths was one from the Frankfurt Fire Brigade, which has close

links with the Scottish city.

Among the mourners was Mr. Gordon Campbell, Secretary of State for Scotland.

Firemaster Cooper read one of the lessons at Holy Cross Church.

Firemen acted as pall-bearers and a lone fireman piper played a lament as six of

the flag-draped coffins were prepared for interment at Glasgow Necropolis —

where the 19 victims of the whisky bond fire are laid to rest. The seventh

coffin was taken for cremation at Craighton.

At the Necropolis brief services were conducted by Bishop Ward and Dr. Morris.

THE QUEEN’S MESSAGE

The Queen sent this message to the Lord Provost:

“I am much distressed to learn of the tragic deaths of seven firemen in the fire in Kilbirnie Street this afternoon.

“Please convey my deep sympathy to the families of those who have lost their lives.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This acknowledgement has been received by “Fire” from Firemaster G. P. Cooper, QFSM, Glasgow Fire Brigade:

THE FIREMASTER has received many expressions of sympathy from Fire Brigades throughout the United Kingdom and abroad, from kindred organizations, from all sections of the business community and from individual citizens resident both in Glasgow and elsewhere.

IT WILL NOT BE POSSIBLE, in many cases, to send individual acknowledgements but, on behalf of the relatives of the firemen who died on duty and all members of the Fire Service, sincere thanks are expressed for such messages of sympathy and for the numerous and beautiful floral tributes received on this sad occasion.

(FIRE magazine October, 1972. Pages 211 & 212.)

JURY’S FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A verdict of death from suffocation

by smoke was recorded by the jury of four men and three women after a retirement

of one hour and 30 minutes at the end of the six-day Inquiry during which over

70 witnesses gave evidence. The jury also recorded one recommendation and five

findings.

RECOMMENDATION: That working co-operation should be closer between the

fire brigade and other local departments responsible for approving fire

prevention alterations in buildings, and that failure to comply with fire safety

requirements in a specified time should incur some form of penalty.

FINDING 1.

The fire was caused by a light dropped by some person or persons unknown.

FINDING 2.

Had a fire screen been erected round the lift and stairs, as specified by the

fire brigade, there would have been added protection for the firemen fighting

the fire.

FINDING 3.

The density of stock stored at the warehouse increased the fire hazard there.

FINDING 4.

The failure of the Department of the Environment to circularize Glasgow Fire

Brigade with the results of “important experiments at the Fire Research Station

dissipated any energies that the fire prevention department could have

progressed in the matter of dealing with hardboard ceilings”.

FINDING 5. “We commend the fire service on their prompt action to deal

with this fire. No words can express appreciation of the valiant and untiring

efforts of the firemen to protect life and property.”

This full report on the Kilbirnie Street fire by Firemaster G. P. COOPER, QFSM, Glasgow Fire Brigade, was prepared for the Fatal Accident Inquiry and we are grateful to the Firemaster for making it available.

THE KILBIRNIE STREET FIRE

The Sher Bros. building is at 70/72

Kilbirnie Street, at the north-west junction of Kilbirnie Street and Ritchie

Street. The building is a separate occupancy bounded by Kilbirnie Street to the

south and Ritchie Street to the east with other premises of single-storey

structure on its two remaining sides. Access for fire service equipment was thus

limited to some extent at the north wall and to a greater extent at the west

wall.

The building consisted of ground floor and two upper floors. The four outer

walls were of load-bearing brick construction. Two of these walls were apexed

gables at the north and south ends, the frontage being on the south gable.

The ground floor consisted of a loading bay area to the south. This area was

bounded by stock rooms to the north and east. An open timber stairway led from

the loading area to the two upper floors. Access to the lift was also here. The

lift served all three floors. The building was 72 ft long by 62 ft wide.

The original structure dates back to 1899 and Sher Bros. took occupancy in 1970.

During its history the building was subject to numerous alterations, including

the erection of various separating partitions. In 1970 Sher Bros. dismantled

these partitions at first-floor level.

However, a partitioned and ceilinged section measuring some 48 ft by 34 ft by 12

ft was retained within the attic floor. The materials comprising these

partitions and ceiling were timber framing with soft wood-fibre building boards

fixed thereto.

A model of the building, built for the Inquiry, shows how this partitioned

section, combined with the stock disposition, created a most unusual problem for

firemen working in thick smoke. (See floor plan of top floor on page 490.)

The first floor survived the fire, being of very strong concrete

construction with an inherently high fire resistance. The ceiling was lined with

hardboard. It was at this level that the situation dramatically changed with the

rapid fire spread which caused the deaths of the seven men on the attic floor

above.

Exhaustive inquiries were made into the circumstances which caused the

first-floor fire to develop in a matter of seconds from a small outbreak at

ceiling level into a serious and extensive involvement. These inquiries were

directed as follows:

TOWN GAS

The possibility of a gas

leak causing a “flash-over” type of condition was investigated. This was ruled

out for: the following reasons:

No one smelled gas at any time before or during fire-fighting operations;

No part of the gas installation was involved in the fire until after the

eruption on the first floor (the installation did not extent to the attic

floor);

Examination of the meter did not reveal any untoward consumption to support the

theory that a leak might have developed but remained undetected before the

fire.

EVOLUTION OF FLAMMABLE VAPOURS

An examination was

undertaken of the theory that heat from the fire above might have produced

fuming on the underside of the attic floor, and that flammable vapours so

evolved might have caused conditions similar to those which might have arisen

with a town gas leak.

It was considered that this might have happened in two different ways:

That the tar content in the attic bitumastic floor might have caused fuming on

its underside with the vapours gathering in volume under the first-floor

ceiling; and

Perhaps heat was conducted through the bitumastic floor, thus causing the wood

underneath to fume, with similar effects, at the first-floor ceiling.

The Fire Research Station was asked if they would assist and they agreed to

carry out tests on our behalf. The flammable vapours theory was discarded

because:

A sample of the bitumastic flooring was subjected to a Fire Propagation Test and

it was found to be virtually incombustible; and

It was known to be a good thermal insulator and could not have sufficiently

raised the temperature of the wood underlaid to cause fuming in the time

available.

FLAMMABILITY OF SALVAGE COVERS

During the initial stages

of fire-fighting on the attic floor the Glasgow Salvage Corps were protecting

the stock on the first floor, directly below the fire, by covering it with

salvage sheets. These sheets were made of plastic material and eye witnesses saw

fire travelling rapidly along them.

A test rig was constructed at the Fire Research Station and two separate tests

were carried out. The rig comprised a Dexion metal box frame with cardboard

boxes on top. A plastic salvage sheet similar to those used at the Sher Bros.

fire was draped over to simulate the conditions prior to the first-floor fire in

the Sher building. (The Fire Research Station report on the tests is on page

491.)

In the first test the rig was topped by an incombustible asbestos sheet ceiling.

A radiant gas heater was placed at ceiling height at one end of the rig and

ignited. The resultant fire developed in a quite conventional manner with a

moderate rate of flame travel.

The salvage covers flamed and disintegrated. Portions of the covers fell to the

floor and the flames went out fairly quickly without consuming the remains of

the material. This test proved that the salvage covers were not the instrument

of rapid fire spread. However, they produced noxious fumes whilst burning and

added to the fire load which suggests that this material might be replaced with

one more suitable.

The second test was conducted in exactly the same way as the first, except that

the asbestos ceiling was substituted with sheet hardboard to simulate the

hardboard ceiling in the Sher first floor.

In little over four minutes from ignition of the gas heater, fire had flashed

rapidly along the underside of the hardboard, igniting the salvage cover as it

travelled. The salvage sheet reacted quite differently when heated from above by

the burning hardboard. It flamed much more rapidly and in disintegrating it fell

to the floor where it continued to burn.

Hardboard had been tested previously at the Station (see page 493) and had

proved to be unsuitable as a wall and ceiling lining for escape corridors. The

test team had therefore expected it to behave in this manner.

The conclusion of the test was that a combination of the specimen salvage sheets

under a hardboard ceiling would lead to a very rapid fire spread, consistent

with the eye-witness accounts of the first-floor fire in the Sher building.

Events at the Sher fire confirm the results of the previous corridor tests at

the Fire Research Station, but further indicate quite clearly that untreated

hardboard presents a hazard hitherto unappreciated in that it may cause rapid

fire spread across its exposed surface with the ceiling alone thus lined.

It follows, therefore, that the salvage covers were only a secondary factor

although their behaviour seemed quite spectacular to eye-witnesses. The

hardboard ceiling which completely covered the first floor was the agent of the

rapid fire spread.

The attic floor was structurally strong but was basically composed of

combustible materials. It was borne on unprotected steel beams set into the

outer walls. These beams were further supported by intermediate cast-iron

columns. Timber joists, 10 in deep by 2 in thick, were laid over. Conventional

tongued and grooved timber floorboards were laid on the joists. The partitioned

section had, in addition, plywood sheets laid over the floorboards with a

finished surface flintstone bitumastic screeding, 5/8 in thick, laid over the

plywood.

This floor would be considerably weakened when subjected to high temperatures on

its underside. It was destroyed in the fire.

The roof was close boarded and slated with timber rafters and steel trussing

under tension. It was also destroyed in the fire.

The Sher occupancy was described as a “Cash and Carry” warehouse. Stock

consisted mainly of clothing and drapery with some fancy goods. Principal

materials involved were natural and synthetic fibres, none of which in itself

constituted a very high fire risk.

However, much of the stock was in cardboard boxes and storage was of such high

density throughout that the fire loading was extremely high. Some stock was

stored on shelving supported by lightweight metal framing and some was simply

stacked in stows on the floor with passages between.

The attic floor consisted of two main compartments. At the head of the stairs

there was a landing which was enclosed by a partition. A door to the north gave

access to a “U” shaped area (hereafter referred to as the West Store) and a door

to the east led into a ceilinged section (referred to as the East store).

There was no ceiling in the West Store and headroom varied from little more than

2 ft to 24 ft at the apex of the roof. The stock in this area was also at

varying levels. Some was stacked close to the walls with a mere 2 ft headroom,

while elsewhere it was racked to a height of about 12 ft.

“West” store is something of a misnomer as this section included an area bounded

by the north gable which formed the base of a “U” and extended along the east

wall to form the second side of the “U”. The latter area was a confined space.

So much so that the employees knew it as “The Tunnel”.

Projecting into the hollow of the West Store “U” was the East Store. In addition

to the access door from the landing there was a doorless opening at the north

end of the East Store which communicated with the north end of the West Store.

Thus there was created an avenue for fire to spread from one section to the

other quite regardless of the combustibility or otherwise of the partitions.

The most significant feature in the East Store is the ceiling. This effectively

screened a large area of the roof and would make it most difficult to strike

fire which developed in the void so formed between ceiling and roof.

Fixed to the rear on the north gable wall was an external fire escape stair.

This was an all-metal structure with one outward opening fire escape door

leading onto it from each of the upper floors. These doors were of timber with

an external metal face. Both were firmly secured on the inside.

The building was examined by a Master of Works Department inspector during the

latter stages of fireground operations on August 25 and was declared unsafe.

Demolition work commenced that same day.

This report may be read by persons who have never experienced those effects of

smoke which have to be accepted by firemen as a facet of their work-a-day

conditions. Most people have, however, the experience of being confused in thick

fog. The fireman is accustomed to working in these conditions and is trained to

search buildings for pockets of fire which may not be visible in the resultant

smoke until he is very close to the flames.

The alternative would be to allow property to burn until fires reached such

proportions that the flames manifested themselves at windows or burned through

roofs where the firemen could tackle them from outside. Such a stratagem would

surely have to be accompanied by a complete disregard for the value of the lives

and property of other people.

It is accepted that the fireman, with his training and experience, will enter

smoke-logged buildings almost totally deprived of his vision, to apply his other

sensory faculties in a search for fire.

(a) He is aware that the fire is drawing air to enable it to burn and

knows that as he approaches it his discomfort in breathing in a smoke laden

atmosphere may become easier as the in-drawn air becomes more focal.

(b) He listens for the noises of crackle or roar which may give him

direction.

(c) He uses the exposed areas of his face and hands to measure for

heat and moves in the direction of increasing intensity.

(d) Finally, he is close enough to see the fire.

Breathing apparatus is available for use in severe smoke conditions which may be

toxic or so concentrated as to render breathing without it impossible. It has

the disadvantages of being something of an encumbrance and deprives the wearer

of the perception described at (a) above.

It will be appreciated that the more complex the building the more difficult is

the task. In thick smoke the layout on the attic floor of the Sher building

would assume the character of a maze.

DRAWING

A plan drawing by Glasgow

Fire Brigade of the top, or attic, floor of the warehouse. Kilbirnie Street is

to the left (south) and Ritchie Street to the east (bottom).

The fire started at the top-right. In his report Firemaster Cooper comments: “In

thick smoke the lay-out on the attic floor would assume the character of a

maze.”

On the first floor of the warehouse the disposition of the stock was similar,

but there were no partitions like those forming the East Store and the Tunnel on

the top floor, and offices and toilets faced on to the Kilbirnie Street wall.

THE OUTBREAK OF FIRE AND ATTEMPTS TO RESCUE FIREMAN ROOK

The fire was discovered by a female

employee in the building. She had left the ground floor to obtain an item or

items for a customer. This necessitated a visit to the first floor. Whilst she

was on the first floor she heard a “popping” sound which seemed to come from

above. What caused this unidentified sound could not be ascertained, but it

prompted her to go up to the attic floor.

When she was approaching the attic she saw smoke and flames. Two male employees

who had been engaged on the first floor followed her upstairs and they tackled

the fire with portable extinguishers.

The female employee returned to the ground floor where she reported the

outbreak. At 1121 a 999 call reporting the fire was received. A further two 999

calls were received at 1123, both reporting the same fire.

The 999 telephone call was received at Headquarters Control at 1121. South Fire

Station was informed and responded at 1122 with a Major Pump, a Water Tender

Ladder and Turntable Ladder. DO Quinn followed immediately after in his car (a

total of 15 men).

The distance from South Fire Station to Kilbirnie Street is half a mile and it

is estimated that the journey would take about two minutes. Appliances would,

therefore, arrive at about 1124.

On arrival, Station Officer Carroll ordered a hose line to be taken inside the

building and he made a preliminary investigation to assess the situation. Smoke

was issuing from the roof and he went to the attic floor by way of the internal

stairs. The hose was taken up and positioned inside the door of the West Store.

Although the stairs were clear of smoke it was dense after some little way into

the West Store. Carroll ordered two men into breathing apparatus to take charge

of the branch and the fire was tackled by Firemen Gray and Murray while awaiting

the arrival of the BA men.

Firemen Gray and Murray washed above them just inside the West Store passage.

The water came back down hot, indicating that there had been some cooling

effect. They penetrated about 10 ft farther and saw the glow of fire ahead. This

fire was struck and the glow extinguished. However, conditions were still hot

and smoky.

The BA wearers arrived and took over the branch. During this phase DO Quinn

arrived and took charge. Carroll conferred with him and it was decided to “make

pumps four”. This would bring on two more appliances with extra men and

equipment in case operations had to be extended in difficult smoke conditions.

The “make pumps four” message was received at Headquarters at 1126. One

appliance was ordered on from Queen’s Park and one from West Marine Fire

Station. Both stations responded with a WTL at 1128. Queen’s Park had to travel

a little less than a mile and West Marine almost 2 miles.

It is estimated that the Queen’s Park appliance would take 3-4 minutes, arriving

at the fire at 1131-1132. West Marine travelled via Kingston Bridge and would

attain a higher average speed, there being almost a mile of urban motorway en

route. Their estimated time of arrival is approximately 1133 hours. The effect

was to increase the number of men from 15 to 24.

Salvage Corps

The Glasgow Salvage Corps had

dispatched one salvage tender on receipt of the initial call which was relayed

from Fire Brigade Headquarters. When informed that a “make pumps four” message

had been received they sent on a second tender and the Chief Officer, Mr.

Edmiston, decided to attend. Mr. Edmiston left Salvage Headquarters, Maitland

Street, at 1130.

Mr. Lim of Singapore Fire Brigade was visiting the Salvage Corps at that time

and was accompanied by Station Officer Campbell of Glasgow Fire Service. It was

decided that Lim and Campbell should go with Mr. Edmiston.

As they approached the south end of Kingston Bridge they found the slip road

into West Street blocked by an articulated vehicle which had “jack-knifed”,

blocking the road. They were obliged to take another route and became involved

in a diversion. The journey was later timed by the Police. It took 15 minutes.

Estimated time of arrival, 1145.

When Carroll ordered BA, Firemen Rook and Howie donned one-hour oxygen sets.

While proceeding to the attic floor Howie discovered that his noseclip assembly

had become detached. He had to return to the Street to obtain a replacement.

L/Fireman Smith told him that he would take his place and Smith went in and

joined Rook. Howie got his replacement and also went in.

There were then three breathing apparatus wearers who took over the branch,

Smith, Rook and Howie. They advanced farther into the West Store and found fire

at the north-west corner. This was dealt with and they then discovered that the

fire had spread across the north end of the floor.

Quinn called for a BA wearer to investigate the East Store. Howie returned to

the landing at the stair head where he entered the East Store. Fireman Murray

(who was not wearing BA) accompanied him part of the way while Howie penetrated

this section. It was discovered that fire had spread into the north part of the

East Store.

Howie returned to Quinn and made a report. Quinn called for another hose line

and a further two BA wearers to deal with this development.

Carroll went to the street to organize this second hose line. After ordering it

to be taken upstairs he saw the Queen’s Park appliance arrive. He directed it

into Ritchie Street and ordered two men into BA (estimated time, 1131).

L/Fireman Brady and Fireman Mitchell donned BA and Brady, assuming that the

approach was to be made via the external fire escape stairs, ordered a line of

hose to be taken up the fire escape. He and Mitchell then ascended the fire

escape stairs to the top floor to find the door fastened on the inside. He

returned to the first-floor escape landing where the door had been opened from

the inside by employees.

He entered the first floor through this door and, accompanied by Mitchell, was

unable to locate the internal stairs. The Salvage Corps were covering stock on

the first floor at this time. They returned to the street and re-entered by the

front entrance, and, finding the stairs at ground level, ascended to the attic

floor.

The branch which had been taken up the fire escape stairs was used to direct

water through a louvred ventilator near the apex of the north gable.

When Brady and Mitchell arrived in the East Store, the fire in this situation

was already being tackled. They took the branch and remained in this position

for about 20 minutes. (It is calculated that they would arrive in the East Store

at about 1135 and remained until about 1155.)

During this time the fire in the East Store seemed to have been extinguished but

conditions were very smoky and it became so hot that they were obliged to

withdraw to the stair landing.

It seems likely that the box-like East Store was surrounded by fire which could

not be seen from within.

When they returned to the landing they learned that Fireman Rook was missing.

The fire was being tackled in the West Store. The jet was directed at the fire

which had spread across the north end. Brady, from the East Store, could see

this through the doorless opening to the north. He also attacked this fire at

this stage and the two jets were impinging.

It is likely that the fire was travelling towards the tunnel (shown on model)

where it would be impossible to strike it without further penetration.

Quinn was concerned to alleviate the dense smoke conditions and had, in the

initial stages, told Carroll that he wanted the roof opened in an effort to

achieve a degree of ventilation.

When the West Marine appliance arrived at 1133 Carroll ordered the

officer-in-charge of the appliance, Sub Officer Stewart, to open a hole in the

roof. They found it an easy matter to remove the timber boards from a former

skylight position, after gaining access by a 45 ft extension ladder pitched at

Ritchie Street. During this early operation no smoke or heat issued from the

opening.

However, on descending from the roof, Carroll reappeared and told Stewart that

he wanted a second hole made. Stewart and his crew re-engaged themselves in this

task, but found it more difficult. They had to remove a section of slates and

then cut through the timber sarking boards before prising off the boards which

were nailed to the rafters.

During this second operation, heat and smoke were rising through the opening,

adding difficulty at their position on the roof. This also suggests that the

fire was travelling towards the tunnel.

The Emergency Tender left South fire station at 1202 and would arrive at about

1203-1204. Stewart recalls seeing it arrive very soon after he came down from

the roof.

Mr. Lim and Station Officer Campbell arrived in the Salvage Corps staff car with

Mr. Edmiston at 1145. Lim alighted from the car and took the first of a number

of photographs. All three entered the building and Lim went to the attic floor

with Campbell.

Lim entered the West Store and could hear a branch working somewhere ahead. He

waited there for a few minutes and then decided to return to the street. He

noticed that the stairs were quite clear of smoke as was the first floor area.

Mr. Edmiston offered Lim and Campbell the loan of protective clothing, providing

a waterproof coat for each and an industrial-type helmet for Lim.

Campbell re-entered the building and went back to the attic floor. Lim took a

photograph in which fire can be seen to have broken through the roof near the

north-west corner.

Lim returned to the attic floor. He estimates that he had been away from the

attic about five or six minutes before arriving back. When he got back to this

level he saw Quinn and heard him shouting orders which indicated that there was

a man missing. At this point the time is estimated at 1150-1152.

Lim then saw two men stumble out of the flat. They were wearing BA. One of these

was probably Fireman Liddell who received superficial burning injuries. Lim,

along with others, assisted this man to the street.

The BA men in the West Store were being assisted by others who were not wearing

BA. Leading Fireman Welsh and Firemen Gray and Murray were among the latter.

Welsh made his way forward and joined Smith at the branch. Welsh saw fire to the

left at the west wall. When the jet was applied the force of water made a hole

in the roof. This suggests that the roof at this point had been considerably

weakened by burning.

Gray was also in the West Store at this time and in a position a little nearer

the stairs where he could assist in moving the hose line if required.

Murray was feeling the effects of working in these conditions and went down to

the street to get some fresh air.

Operations had been in progress for something like 25 minutes and Quinn must

have been concerned that the fire was still not under control. He ordered

everyone out.

Campbell returned to the attic floor before Lim. Campbell did not hear Quinn’s

order requiring everyone to come out. Campbell was either approaching the attic

and could not hear the order or he had entered the West Store and for some

unknown reason did not hear it.

‘Rook, out!’

In response to the order Smith, who

was at the branch, left it and went back to the stairs. Smith was feeling the

effects of heat and descended part way down the top flight where he sat down

exhausted.

Gray also responded to the order but had the impression that Rook had not heard

it. Gray thumped Rook on the back and said, “Rook, out!” Rook turned in the

direction of the stairs and Gray, assuming that Rook would follow him, made his

way to the stairs.

Campbell, in the meantime, had made his way forward and saw fire to his left. He

got the assistance of a BA man (Rook) and turned the jet on the fire.

Quinn, it is assumed, would be noting the BA men in particular and asked where

Rook was. Smith said he presumed that Rook had preceded him on the way out.

At this time Campbell and Rook were about 20 ft inside the West Store passage.

Part of the stock on the east side of the passage must have collapsed. Rook was

buried under the packages and Campbell was struck on the head and stunned.

Firemen Liddell and McMillan had been standing by in the street, with the TL,

ready for use, throughout the earlier part of operations.

However, they had not been called upon to engage with their appliance and

approached Carroll and asked, if the TL was not to be used, they might be

engaged inside the building.

This approach was probably made some time between 1145 and 1150. Carroll told

them to don breathing apparatus and go to the attic floor.

By the time Liddell and McMillan got dressed in the apparatus and arrived in the

attic the search for Rook was being initiated. Quinn told them to go in and get

Rook. At this stage fire had broken out in the West Store just inside and to the

left of the door from the landing.

The branch from the East Store, which had been brought back to the landing, was

being used to quell this outbreak. Fireman Howie was inside the door with the

branch.

Liddell and McMillan passed Howie and entered the West Store. Within a short

time Liddell was overcome by heat and had to be assisted to the street.

Liddell’s face was scorched. This incident was quickly followed by an entry by

Brady and Mitchell.

When Brady and Mitchell came out of the East Store they were ordered into the

West Store to get Rook. Brady recalls passing two BA men who were lying on the

floor and moving material. (It seems likely that these would be Firemen Howie,

who was tackling the fire situation, and McMillan, who did not go out with

Liddell.) Brady came to a pile of stock about chest high and he started to clear

this, but he was rapidly overcome by heat and had to be assisted out.

Campbell appears to have been lying unconscious during this time and he

remembers coming to the realization that he was now lying on his back on top of

stock and that Quinn was beside him, telling him to shut off the jet. Quinn must

therefore have gone into the West Store passage after the collapse of Brady.

Campbell shut off the jet and went to the landing. He next remembers finding

himself out in the street but cannot recall how he got there.

The situation was now quite critical. Rook was still missing and the attempt to

find him had been aborted by the collapse of two of the rescue party.

Furthermore, all the men now on the attic floor were physically exhausted.

Carroll during all these operations had been moving all over the fireground

organizing the crews and equipment as directed by Quinn.

Quinn ordered on the Emergency Tender to obtain more breathing apparatus

(message sent at 1200). Carroll was not wearing BA but penetrated the West Store

passage as far as he could to look and listen for signs of Rook. There was none.

Everyone went downstairs with the apparent exception of McMillan. It seems

likely that Quinn left McMillan to contain the fire at the West Store passage

door while he (Quinn) went downstairs to organize a fresh rescue attempt. The

time was about 1200.

Murray had returned to the street before the discovery that Rook was missing.

When he learned that Rook was still somewhere on the attic floor, Murray put on

the one remaining BA set (the ET had not yet arrived) and, acting on his own

initiative, went back up to the West Store.

In the West Store passage he joined another man in BA (McMillan). Together they

tackled the situation. The fire on the west side of the passage was kept under

control and Murray reached the point where the collapsed stock was shoulder

high. He started passing the packages back.

In the meantime Quinn had gone down to the street and called for fresh BA men.

The ET had arrived with more BA sets and Firemen Hooper and Findlay seem to have

responded first, with Leading Fireman Crofts and Fireman Bermingham closely

following.

All four went to the attic floor to reinforce Murray and McMillan. The recorded

time of entry was 1205.

Quinn sent a message at 1207 which said,”. . . one man trapped, one man

collapsed”. (In fact, two men had collapsed, Brady and Liddell.)

Between 1205 and 1217 approx the party engaged in search and rescue operations

on the attic floor consisted of the following:

Wearing BA: Leading Fireman Crofts and Firemen Bermingham, Murray, McMillan,

Findlay and Hooper.

Not wearing BA: Divisional Officer Quinn and Station Officer Campbell (in the

latter stages only). In addition, Station Officer Carroll was moving between the

attic floor and the street to maintain a controlling link.

During the final search and rescue phase Campbell spoke to Carroll in the

street. Carroll was concerned on several counts.

(i) The fire situation seemed to be deteriorating on the attic floor.

(Carrying out fire-fighting and rescue operations simultaneously is always

extremely difficult.)

(ii) Fire had broken through in a small area at the northwest corner

of the first floor. (This outbreak was receiving attention.)

(iii) There would be insufficient fresh men to deal with any

unfavourable change in the current situation.

Carroll said that he felt he should “make pumps eight” without delay. This meant

doing so without prior approval from Quinn.

Campbell agreed that this should be done. The “make pumps eight” message was

sent by Carroll personally at 1214.

Campbell left Carroll and returned to the attic floor, Carroll also went back.

On being informed of the “one man trapped, one man collapsed” message, received

at 1207, the Deputy Firemaster, Mr. McGill, turned out to Kilbirnie Street. He

travelled by car from Ingram Street. When he was a short distance beyond Gorbals

Cross he heard the “make pumps eight” message.

He was not displaying his roof beacon light nor was he sounding his two-tone

traffic horn. The distance remaining to Kilbimie Street was about one mile. It

is estimated that this would take between three and four minutes and he would

arrive at about 1218.

First floor fire

At about 1212 Carroll had visited

the first floor and discovered that fire had burned from above through the

ceiling at the north-west corner. The extent was minimal but be returned to the

street and ordered a line of hose to be taken up to deal with it. He left Sub

Officer Stewart to the detail.

Although the fire on the first floor was very small Carroll was concerned

because it indicated to him that the fire was burning at the north-west corner

of the attic floor while the rescue operation was proceeding not very far from

this position.

It was at this point that he spoke with Campbell and made pumps eight.

At 1214 Campbell went upstairs to the attic. He saw BA men handling the stock in

the West Store passage. Campbell told them where he thought Rook might be and he

heard what seemed to be a BA warning whistle.

In the smoke conditions Campbell could not see more than a few feet ahead.

Although he did not realize it at the time Rook had been found and was being

brought out.

Campbell was satisfied with what he saw and went back downstairs.

Carroll followed Campbell upstairs after sending the message at 1214. (He did

not know that Campbell had preceded him.) As he emerged onto the first floor he

saw Leading Fireman Welsh standing in readiness near the north-west corner. The

hose was not yet charged with water. Carroll noticed that fire had fallen into

the corner and, although not apparently serious, it was worse than when he had

seen it first.

He continued up to the attic floor and reported to Quinn. Carroll told Quinn

that he thought conditions were deteriorating. Quinn said that as soon as he got

Rook they were all getting out. Carroll informed Quinn that the fire had broken

through to the first floor and Quinn told him to deal with it.

Carroll went back down to the first floor and was immediately struck by the fact

that he could no longer see Welsh with the branch. (Welsh had moved to a more

advantageous position in line with the stairs.)

At that moment Leading Fireman Smith was at the head of the first flight of

stairs and was returning to the first floor after checking that the water was

coming. Also, unknown to Carroll, Campbell had just come down from the attic and

was rounding the corner of the lift shaft at the first floor.

Suddenly the fire spread with tremendous speed. Welsh, taking the branch with

him, ran to the stairs. Carroll also ran to the stairs. Welsh, Carroll and Smith

had to run down to escape the blast of heat which developed with the sudden

spread.

They had just got part way down when the water came on and they went back up to

attack a massive outbreak which involved the upper level of the first floor in

every part they could see.

When Campbell came down the stairs from attic to first-floor level he recalls

that the stairs were clear of smoke and conditions were cool.

As he rounded the corner of the lift shaft he was looking northward into a

passage. He saw fire flashing rapidly towards him at a high level. It travelled

over him as he crossed the front of the lift shaft, forcing him to adopt a

running crouch position.

He ran on downstairs, oblivious to the presence of Carroll, Welsh and Smith, and

out into the street.

Campbell knew that the men he had just left were trapped.

Reverting to Fireman Murray’s actions, he reported that he was not very long

engaged on the attic floor when he was joined by Fireman Bermingham. Bermingham

arrived fresh and he was a particularly strong man. Bermingham proceeded to

remove the pile of collapsed stock and uncovered Rook who had been buried under

it.

Rook’s “Diktron” distress signal unit had been actuated and could be heard quite

clearly. Bermingham grasped Rook, who was jammed in some way, and pulled him

forcibly six, seven or eight times before he was eventually freed. During this

operation Murray was crouched, holding up the Dexion racking which was very

unsteady.

As soon as Bermingham freed Rook he dragged him along the West Store passage

towards the stairs, leaving Murray to support the Dexion racking until he got

clear.

Murray stated that conditions were very hot and the smoke was dense at this

point. After Bermingham left with Rook, Murray heard a scream. One may only

conjecture that Bermingham received assistance from the other BA men with the

removal of Rook, and that Rook was probably hurt whilst being dragged along the

floor.

When Murray judged that sufficient time had been allowed to get Rook clear he

dropped to his hands and knees and crawled to the stairs. When he reached the

head of the stairs Murray tumbled down onto the half-landing. His mouthpiece and

noseclips were dislodged in the fall and he replaced his mouthpiece. He saw fire

above him.

Following the hose, he made his way down to the first floor. He recalls losing

the hose at the first-floor level where some stock had collapsed and buried it.

He continued and found the hose again. He does not remember any more. His face

and hands were burned.

Carroll, Welsh and Smith had ascended the stairs again to attack the spread on

the first floor. In their sudden enforced retreat none of them had noticed

Campbell go past.

When they reached the top of the flight of stairs they saw Murray’s legs. Murray

was badly burned on the hands and his face was also injured. Carroll and Welsh

had to assist him to the street. Welsh recalls that he heard “thumping” on the

stairs above just as Murray appeared and he heard someone moaning. Welsh was

also aware of a DSU sounding and then the sound stopped suddenly. Smith remained

with the branch but was unable to make any impression on the fierce fire on the

first floor.

The time was about 1217.

Some short time before 1217 Fireman Howie was in Kilbirnie Street. He thought

that conditions were deteriorating on the roof and decided to get the TL

elevated. When Campbell came out into the street Howie was already on the

elevated ladder.

No retreat

Knowing that the men in the attic

had been cut off from their line of retreat he called Howie down and Campbell,

mounting the ladder himself, went to one of the attic windows to assess the

situation and make the ladder available for rescues. It was at this point that

Deputy Firemaster McGill arrived. Estimated time 1218.

Campbell could see that the situation on the attic floor had developed into a

serious and extensive fire with no possibility of rescue from the attic windows.

Water was directed through a window in an attempt to extinguish the fire.

To summarize:

1. The fire had been initially tackled in a conventional way.

Quinn’s plan was obviously to drive the fire towards the north gable wall

contain and extinguish it.

2. The plan was thwarted by the unusual design of the attic floor

and the density of the stock which allowed the fire to spread.

3. The smoke was too dense to permit an assessment of likely fire

spread in the unusual layout.

4. At the stage where Rook was first missed it seems likely that

Quinn was about to change his tactics. His purpose in ordering everyone out of

the attic floor was probably that which every fire officer has had on numerous

occasions; to obtain absolute silence so that he could listen at the top of the

stairs and make an appreciation of the situation. (Men working make this

impossible except in the most obvious circumstances.)

5. It is not possible to conjecture with absolute certainty what

change of tactics, if any, Quinn might have adopted. However, the fire had been

fought for nearly half an hour and was still not under control, and it is

reasonable to suppose that he was considering a withdrawal to attack the fire

from outside through the windows, roof openings and fire escape door.

6. Quinn’s intentions were thwarted by Rook becoming trapped.

7. The initial rescue attempt in which Brady and Liddell were

overcome was frustrated by the need to carry out a rescue attempt and a

fire-fighting operation simultaneously. (The fire having broken out between

Rook’s position and the stairs.) Water applied on the fire changes to steam and

so worsens the conditions for the rescuers.

8. The defeat of the first rescue attempt must have put Quinn on the

horns of a dilemma—to mount a second rescue attempt with its attendant risks, or

to abandon Rook.

9. Quinn’s decision to mount a second rescue attempt marks him as a

man of outstanding courage and tenacity.

10. Leading Fireman Crofts, Firemen Bermingham, Findlay and Hooper

must have known that the situation on the attic floor was difficult and

dangerous. There was no vestige of hesitation in their response to the call for

action.

11. McMillan did not have to remain on the attic floor. He would have

been procedurally correct to have come out along with Liddell. He elected to

stay.

12. Murray’s actions on hearing that Rook was missing distinguish him

as a fireman of exemplary bravery. No one is expected to don BA and enter a

building single-handed as he did. Especially when he had returned to the street

suffering from the effects of his exertions in the earlier part of the

operations. He was fortunate to escape.

13. Campbell of his own volition returned to the attic floor to ensure

that the rescuers were properly appraised of the situation. He narrowly escaped

losing his life in so doing.

14. Carroll also returned to the attic floor, knowing that the

situation was worsening. He would probably have remained to assist in the attic

had he not been ordered down by Quinn to deal with the fire on the first floor.

Coming down just before Campbell, he also had a narrow escape.

15. Had Carroll, Welsh and Smith not returned after being forced down

by the fire it is possible that Murray might not have escaped, for he collapsed

and has no recollection of their assisting him.

16. The question remains as to how Murray came down and yet he was the

last to leave the interior of the West store. It will be recalled that as Murray

was left supporting the Dexion racking he heard a scream. One can only

conjecture that this scream emanated from Rook as he was being dragged along the

floor, and that he was hurt in the process. It is likely that all except Murray

were mustered on the landing preparatory to making their descent. Perhaps they

were trying to get Rook to his feet or preparing to carry him down so as not to

hurt him any further. Whatever happened, Murray must have crawled past them

unaware of their position in the smoke a few feet away.

17. When the rescue party were struck by the upsurge of heat from the

sudden fire beneath them, there would be no alternative but to leave Rook and

hope to return for him. (If indeed there was time to consider any hope.) The

photograph of Rook’s body shows his BA harness still pulled up under his armpits

as it would be if he was dragged by the straps or hauled to his feet by them.

His position certainly suggests that he never stood independently on his own

feet or the weight of the apparatus would have naturally located the waist strap

at his middle and the cylinder valve group at his left hip. It is likely that

the DSU which Welsh heard was Rook’s. The photograph indicates that he had

fallen in such a way that his DSU, fitted on the front of his right shoulder

strap, would be muffled or perhaps damaged. This would account for Welsh’s

observation that the sound ceased abruptly.

18. The rapidity of fire spread on the first floor was completely

unexpected and the tremendous heat evolved would render breathing impossible

within seconds, even in breathing apparatus.

19. Having found Rook and got him back to the stair landing the rescue

party were only a few yards in distance, and a matter of seconds in time, away

from safety.

20. The final summary point relates to the Dexion metal framework

which supported the stock shelves on one side of the West Store passage. The

stock collapse which trapped Rook seems to have come from this Dexion structure

which was some 12 ft high. There is no report of fire on these particular Dexion

shelves before Rook was trapped. The question is what caused the considerable

collapse of stock? The Dexion manufacturers have a recommended code of practice

for the construction of their frames. Was this adhered to? And, if not, was

there some instability of the framework which was caused by faulty assembly or

insecure attachment to the floor or wall? Rook would not have been trapped if it

had not been for the collapse in this vicinity and, therefore, these questions

seem highly relevant.

Photographs

Firemaster Cooper’s report then

details some of the 14 photographs taken by Mr. Lim and produced in evidence at

the Inquiry. While Lim was taking some of these photographs Deputy Firemaster

McGill was engaged in assessing the situation with the object of rescues. DO

McKinnon had left Central Fire Station after being informed of the “make pumps

eight” message at 1214. Mr. McKinnon departed in his staff car at 1215 with his

roof beacon lit and he used his two-tone traffic horns to expedite his progress.

A test run on the same route with similar conditions took 6½ minutes to

complete. It is estimated that McKinnon arrived at the fire at about 1222.

On arrival McKinnon observed the TL applying water from Kilbirnie Street. He

noticed nothing unusual about the ladder man. (This suggests that Campbell had

descended by that time as McKinnon feels sure that the unusual sight that would

have been presented by Campbell, bareheaded and clad in a long black coat, would

have made an impression on his memory.)

McKinnon joined Deputy Firemaster McGill and assisted him in the execution of

his plans to explore the possibility of rescues.

Supporting appliances responding to the “make pumps eight” message were already

arriving when Mr. McGill took command. He had ordered Carroll to take a

roll-call, but Carroll was suffering from a degree of exhaustion and distress.

The Stage 2 BA Control Board recorded that those missing were:

DO Quinn, Leading Fireman Crofts and Firemen Bermingham, Findlay, Hooper,

McMillan and Rook. The roll-call confirmed the record.

Soon after arriving McGill had entered the building and could see that the first

floor was well alight.

It was apparent that rescues would not be possible per the internal stairs. An

exploration of the fire escape stairs also produced negative results.

McGill’s problem was two-fold:

(a) The fire had to be held in control, but the application of water

had to be kept to a minimum to permit rescue operations and to avoid a worsening

of conditions for survival.

(b) A point of

entry had to be established where rescues were possible with a minimum of

exposure to risk.

It was decided to effect an entry by ladder through a first-floor window and

thence to the stairs. Lim Photo 10 shows this ladder being placed in position at

the front of the building. McKinnon states that this was about five or six

minutes before he arrived and fixed the time at 1227 or 1228. The photograph

clearly shows that the upper part of the building was a raging inferno at this

time.

Climbed in window

Nevertheless, no fire is showing at

the first-floor front windows and the possibility that someone was alive in this

vicinity could not be ignored. Despite the obvious danger Mr McGill and McKinnon

spearheaded an entry and McGill can he seen in Lim Photo 11 about to enter the

window. The time is estimated at about 1230 hours.

McGill, McKinnon and Campbell penetrated the building from this first floor

window. They found themselves in a toilet compartment. Opening the door to their

right they found themselves confronted with a very considerable fire. The

situation was too dangerous to continue until the fire was reduced. They

returned to the street.

An attack on the fire from outside was already being mounted and McGill, after a

survey at the rear, decided to reenter at first-floor level. He and Campbell

went up the internal stairs to the first floor and attacked the fire with a jet.

Having reduced the fire sufficiently in this vicinity, McGill and Campbell then

crossed the floor while covered by another jet.

Simultaneously, McKinnon had entered by the first-floor window and broken out of

the toilet compartment close to the stairs. They joined forces and went up to

the attic floor half landing. There they found the bodies of Firemen Bermingham,

Findlay, Hooper and McMillan. The log records that the first body was found at

1348.

It was now apparent that all hope of survivors was in vain and to expose men to

further danger was not justifiable. McGill ordered a withdrawal until the fire

was brought under control.

No attempt is made to describe the gallantry of this episode. That McGill and

his men had decided to enter the building speaks for itself.

The fire was now tackled with a considerable volume of water. Aerial jets were

applied from two TLs, two HPs and a “Scoosher” monitor. These were supplemented

by hand-held jets surrounding the building.

When the fire was brought under control the building was in a dangerous

condition. The task of recovering the bodies of the victims was in itself a

hazardous one.

The bodies of Quinn and Crofts were found under the debris near the lift shaft

at 1609 and 1622. Quinn’s watch had stopped at 1233. It was probably damaged by

falling debris at this time but Quinn would have died six minutes earlier.

Finally, Rook’s body was recovered on the top floor at 1811.

Firemaster Cooper concludes his report: With the exception of Fireman Howie’s BA

set, which sustained a detached noseclip, there was no failure of any Fire

Service equipment. Water supplies were adequate and available when required.

It would’ not be fitting to close this report without paying tribute to the

Glasgow Police and Ambulance Service and the Master of Works Department who

rendered such able support.

After suffering a bitter blow the morale of Glasgow Fire Service is high, as one

would expect in a service which has produced the ultimate in comradeship and

human sacrifice.

EVIDENCE TO THE KILBIRNIE FIRE INQUIRY

The Fatal Accident Inquiry into the

deaths of the seven fire-fighters was held in Glasgow High Court before Sheriff

William J. Bryden, sitting with a jury of four men and three women. During the

six-day hearing more than 70 witnesses gave evidence, including 24 from Glasgow

Fire Brigade. The evidence was led by the Procurator Fiscal, Mr. Henry Herron.

Mr. Ian MacDonald, QC, appeared for the six firemen, with Mr. Hugh Morton; Mr.

Hugh Campbell represented DO Quinn’s relatives and Station Officers Carroll and

Campbell; Mr. Donald Ross appeared for Glasgow Corporation, with Mr. Ronald

McKay; Mr. Kenneth Cameron, QC, represented Glasgow Salvage Corps; and Mr. Harry

McGhee appeared for Sher Bros.

The major points of the evidence are summarized here and on pages 500, 501 and

518.

Sub Officer G. Alexander,

South Fire Station, inspected the warehouse on December 15, 1971, under the Fire

Services Act 1947. He found the general housekeeping very bad and goods “all

over the place” particularly on the top two floors where he had to clamber over

packages to complete his inspection. There were also goods on the stairs. Both

doors to the fire escape were locked.

He spoke to Mr. Sher about the housekeeping and the doors and one of them was

opened before he left the building.

DO J. Flood,

“B” Division, said that following Sub Officer Alexander’s report he initiated a

Section I (i) D inspection under the Offices Shops and Railway Premises Act. On

March 20, 1972, he visited the warehouse, saw Mr. Sher and explained the

purposes of the two visits. Staff were smoking on the ground floor, but not on

the upper floors; there were “no smoking” notices displayed. He considered the

warehouse a very high fire risk because of the large quantity of goods stored,

particularly on the first floor where the stowage was excessive. He advised Mr.

Sher to seek advice on fire precautions and suggested the form a letter to the

Firemaster should take.

Station Officer W. Smart,

FPO, visited Sher’s on December 16 and again on December 21. Subsequently, two

letters were sent from the brigade, both dated February 8, 1972. The first dealt

with OSRP Act mandatory requirements concerning the positioning of fire

extinguishers and the clearing of stock from stairways, passages and the fire

exit doors. The other letter recommended the provision of a fire screen around

the stair and lift well, a fire exit sign at the Kilbirnie Street entrance,

inspection and testing of the alarm system and instruction to staff.

A letter from Mr. Sher, dated March 20, was received by the brigade asking for

advice on fire precautions; the brigade reply, dated April 27, contained

photostat copies of the two letters of February 8.

Mr. Mohammed Rafiq Sher,

senior partner of Sher Bros., was warned by the Sheriff: “It may be said that

you were guilty of an offence. I have to tell you that if answers are likely to

incriminate you, or to suggest that you are guilty of an offence, you are

entitled to refrain from answering.” Mr. Sher replied: “I have nothing to hide,

I will answer all questions.”

Mr. Sher said he did not receive the letters of February 8. He received the

April 27 letter but it had only one enclosure, a photostat of the February 8

letter referring to the mandatory requirements. The first time he saw the letter

referring to the fire screen was in the Inquiry.

He said it was not true that his house-keeping was bad or that passageways and

stairs were obstructed. If ever he saw goods lying about, he told the staff to

tidy them away. “No smoking” notices were displayed and the only two areas in

which smoking was allowed was in the canteen and at the check-out counter on the

ground floor. He confined his own smoking to these two points.

Mr. Sher said the only part of the warehouse ever to be obstructed by goods was

the loading bay when a delivery was made and his staff cleared the goods as

quickly as they could. Tables on the stair half-landings did not form an

obstruction, he said.

Replying to Mr. McGhee, Mr. Sher said that early in 1971, he had discussions

with his architect about a new building at the rear of the warehouse and about

alterations to the existing warehouse. It was his intention that when the new

building was completed the business would be conducted from it while the

warehouse was altered.

Work on the new building started in April, 1972, and was expected to be finished

by late July or early August but the national shortage of bricks and the

building strike delayed work which was still going on when the fire occurred.

Mr. Munawar Hayat,

a cousin of Mr. Sher, and one of six partners in the business, said that on the

day of the fire he tried to open the first floor fire door with the key which

hung beside it, but he was so nervous and excited that he could not do it. He

forced the door open with a crowbar.

Mr. Mialian Zafar Ali,

partner in the business, said the insurance fire inspectors had been in the

building about two weeks before the fire and had no complaint about the stock.

The fire insurance on the building was previously £60,000 but Mr. Sher had

reduced this to £27,000. Under an averaging clause the most he would be likely

to receive would be some £12,000 or £13,000. The stock was insured for some

£100,000.

Mr. Rennie Matthew,

chartered loss adjuster, said the building was inadequately insured and there

would be a loss on it of some £40,000.

Mr. W. McLuckie,

building surveyor, said the plans for the work were dated November 27, 1971, and

application for a Master of Works warrant was made in the December. The warrant

was dated January 21, 1972, and planning permission given on February 25, 1972.

Mr. James Clunie,

consultant architect, said he had prepared plans for improvements to the

existing warehouse, and for extension at the rear. The improvements were mainly

concerned with increasing the operating efficiency of the premises, but were

also designed to maintain the means of escape. They included the conversion of a

fire exit door to Ritchie Street into a customer’s door, the replacement of the

timber stairway with a concrete one and the building of a brick wall around the

stair and lift well. He did not know of the existence of the letter from the

Firemaster detailing requirements under the Offices Shops and Railway Premises

Act. The only work carried out before the fire was the new door in Ritchie

Street and the extension.

He told Mr. McGhee he said Mr. Sher was concerned to have the building made safe

from fire. The hardboard ceiling to the first floor was in existence when Sher

Bros took over the building. It was not a form of ceiling lining which would be

installed today.

Mrs. E. Walsh

said she had been bookkeeper for the firm for a year and occupied a first floor

office. She only smoked in her office and had never been on the top floor. Some

months before the fire Mr. Sher had told the staff to stop smoking and had put

up “no smoking” notices. Cross-examined by Mr. McDonald she said she had written

a letter to the Firemaster, at the dictation of a fireman in Mr. Sher’s office,

asking for advice on fire precautions. She did not remember seeing any letters

from the Firemaster. She thought that if she had been given them to file then

she would remember them.

Ian Gray, warehouse boy and a nonsmoker, said his duties were clearing up on all

three floors. Sometimes when sweeping up on the upper floors he saw cigarette

ends.

Mr. McGhee: “Did you not

think that in view of the no-smoking rule you should have reported this?“—“I

suppose I should.”

Mrs. A. A. Bradley,

who had worked for Sher Bros for 18 months, said smoking was allowed only on the

ground floor and in the ladies’ toilet. Normally goods were stacked away

immediately after delivery and if any boxes were lying around it was only for a

short period before they could be stacked. All the passages and stairs were

normally clear.

Miss Sally O’Donnell

said on the day of the fire she had no cigarettes, although she normally smoked.

About 1030 she had to go to the top floor to fetch articles for a customer. She

did not see anyone up there and did not notice anything unusual. She had no

difficulty in walking in the passage way between the goods.

Cross-examined by Mr. MacDonald she said she and some of the other girls smoked.

There were ash trays on the ground floor, but not on the upper floors. If they

wanted to put a cigarette out when they were on the upper floors they stamped on

them to put them out. During the time she worked at the warehouse no one spoke

to her about fire precautions and there was no fire drill. She did not know

there was an external fire escape and had never seen its doors open.

Answering Mr. McGhee she said she had never seen any “no smoking” notices in the

building.

Mr. McGhee: “Did you know there was a very strict rule against smoking?”—“The

only thing was that the girls said that if we saw Mr. Sher coming we should put

the cigarettes out quick.”

Mrs. M. Elwood,

sales assistant, said she normally smoked and carried cigarettes in her overall

pocket. On August 25 she twice went to the top floor to get garments, the last

time being about 1050. The temperature seemed normal and there was nothing out

of the ordinary. She was not smoking and did not see anyone up there.

About 15 minutes later she went to the first floor to get a pair of shoes. Two

boys were there, stocking up shelves. She heard a “popping sound like a light

bulb exploding” and saw smoke coming down the stairs. She ran up to within a few

steps of the top landing but thick smoke stopped her. The two boys used fire

extinguishers but they did not have any effect.

John McGrory,

store boy and nonsmoker, was on the first floor with another boy rearranging

stock to make space when Mrs. Elwood came there to get a pair of shoes. Thick

smoke stopped him from reaching the top floor. He let off an extinguisher but it

had no effect.

He told Mr. Morton that he had never seen any cigarette ends when cleaning up.

Some of the staff disregarded the rule about not smoking on the top floors. Mr.

Sher was always going on about smoking on the top floors.

The Sheriff: “There would be no need for him to go on telling people not to

smoke upstairs if they were not already doing it, would there?”—“No, I suppose

not.”

He told Mr. McGhee that about a week before the fire he had been told to tidy up

the top floor and had received a bonus for doing it well. He was quite satisfied

that on the morning of the fire everything was tidy.

Mr. W. Morris,

Higher Scientific Officer at the Fire Research Station, said that he carried out

“ad hoc” tests on salvage sheets in the company of Assistant Firemaster Kelly

and DO Clarke. The results were as in his report (see page 491). He was also a

co-author of Fire Research Note 876 (see page 493).

Cross-examined by Mr. MacDonald, Mr. Morris said that the series of tests

described in FR Note 876 were designed to assess the validity of standard test

procedures. He did not agree that the document contained valuable information

relating to the fire spread of hard-board; the fire characteristics of

hard-board were well established and had been known for many years.

After the report had been completed, he said, it would be referred to in Station

publications and anyone interested could apply to the library for a copy. He

thought that copies had been circulated to some brigades and also to the Home

Office and the Home and Health Department.

Mr. A. S. Edmiston,

Chief Officer of the Glasgow Salvage Association, said that in view of the Fire

Research Station report on the behaviour of plasticized salvage sheets in fire

test conditions his Board were considering the whole question of their use by

the Salvage Corps.

Station Officer R. Carroll,

in charge of the first attendance, said he did not consider the fire a major one

when he arrived. He ordered a line of hose to be taken to the top floor and went

there himself. There was a pall of smoke and heat, but no flame. He did not

anticipate any danger to firemen’s movements, but arranged for BA to be used

because of the smoke.

DO Quinn, who was his uncle, arrived on the top floor with Rook and Smith, both

wearing BA. The DO decided to make pumps four for BA and that the roof should be

pierced for venting purposes and a jet put through the hole.

Quinn said he wanted a further line of hose in the East Store with BA men and he